Why Reliability is a Practice

What is reliability?¶

Reliability is measured from the perspective of your system’s users. A system can be said to be reliable if its users rely on it and it meets their expectations. If this is the case, we often say that the users are happy with the system.

If your users are happy with your system then it is not only continuing to evolve and providing the right features, and so becoming increasingly useful over time, but the system also meets its users’ expectations and allows them to build trust and confidence in the system’s operation. Reliability is a crucial differentiator if its users are to depend on the system. Successful systems are useful, performant and reliable.

Reliability goes Beyond Testing for Release¶

You could, and should, test your systems before release, building your own trust and confidence that what’s being changed will work well according to your own measurements of success. In fact the adoption of Agile and DevOps practices, especially Continuous Delivery, only increases the emphasis on high quality testing of any set of changes when a system is continually prepared and released to its users.

Effective adoption of these practices goes hand-in-hand with practicing reliability. The challenge is that if a system is sufficiently complex, and most modern enterprises’ systems are, then it is not possible to prove that a system will be reliable before it is run. No matter how much proof you have invested in obtaining prior to release, no matter how many unit, integration, feature and system tests you have conducted as part of your continuous integration and build, reliability can only be proved when the system is running, and ideally under realistic conditions.

Is my system Reliable?¶

Your system is reliable if it continues to meet its users expectations over time. Surprising conditions over time threaten your system’s ability to meet those commitments and expectations, testing the efficacy of your system’s robustness strategies.

A robustness strategy is any strategy you’ve deliberately applied in the hope that it will help some aspect of your system better respond to some predicted conditions. For example, you might employ High Availability deployment options for your data storage, circuit breakers for inter-service communications, playbooks to help your people respond, dashboards and other observability tools to aid system comprehension, debugging and real-time alerting, even incident response systems to help your people synchronise and respond to surprising conditions. These are all robustness strategies as they help you respond to known threats to your system’s reliability.

Robustness strategies are applied across the whole of your socio-technical system, including the people, practices and processes that surround it. You aim to add the right mix of robustness strategies so that your socio-technical system is better prepared for known conditions. The better prepared the system, the better it will deal with anticipated conditions. That’s the hope anyway. Of course there’s also the unexpected conditions as well, and for those your robustness strategies have a positive impact on your system reliability, but that is not guaranteed.

There are three difficulties with robustness strategies. Firstly they can appear to be no-brainer techniques to apply everywhere, even where they will not help. The second problem is that robustness strategies are applied in the hope that they will respond appropriately to target conditions that you expect, or at least anticipate, but then those strategies are rarely verified to actually work the way you hope they will before real circumstances. On top of those, it is very rare that combinations of multiple robustness strategies working together to produce a positive result are ever proactively verified before they are needed for real. You hope they will work well, but hope is not the right strategy.

Proactively Verifying Robustness helps Reliability with Chaos Engineering¶

One of the key tasks when practicing reliability is exploring how effective your robustness strategies actually are when they are called upon to work together. You can verify how observable your system is, how your circuit breakers pop, and what the overall impact might be on your reliability objectives using the practice of chaos engineering.

“Chaos Engineering’s sole purpose is to provide evidence of system weaknesses” - “Learning Chaos Engineering” by Russ Miles, O’Reilly Media

Using chaos engineering you can collect the evidence of the real impact on your system’s reliability under adverse conditions. Rather than relying on hope, you build chaos engineering experiments that verify how your system employs its robustness strategies to anticipate, coordinate and respond to difficult conditions.

Beyond Robustness: Resilience¶

Robustness, and even verification using chaos engineering, is limited to helping you prove and improve how your system’s reliability is affected in the face of known conditions. But what about the unknowns? While it’s impossible to verify how your system will respond under any unknown conditions, this is where resilience engineering can help.

Resilience engineering aims to help you develop your system so that it is “poised to adapt”. By building specific capacities, your system can be ready to detect, deal with, and—more importantly—learn from unexpected conditions. Those resilience capacities are manifested across your entire socio-technical system.

Practicing Reliability & Resilience¶

When you practice reliability you proactively prove and improve your organization’s resilience capacity to adapt to unexpected reliability threats.

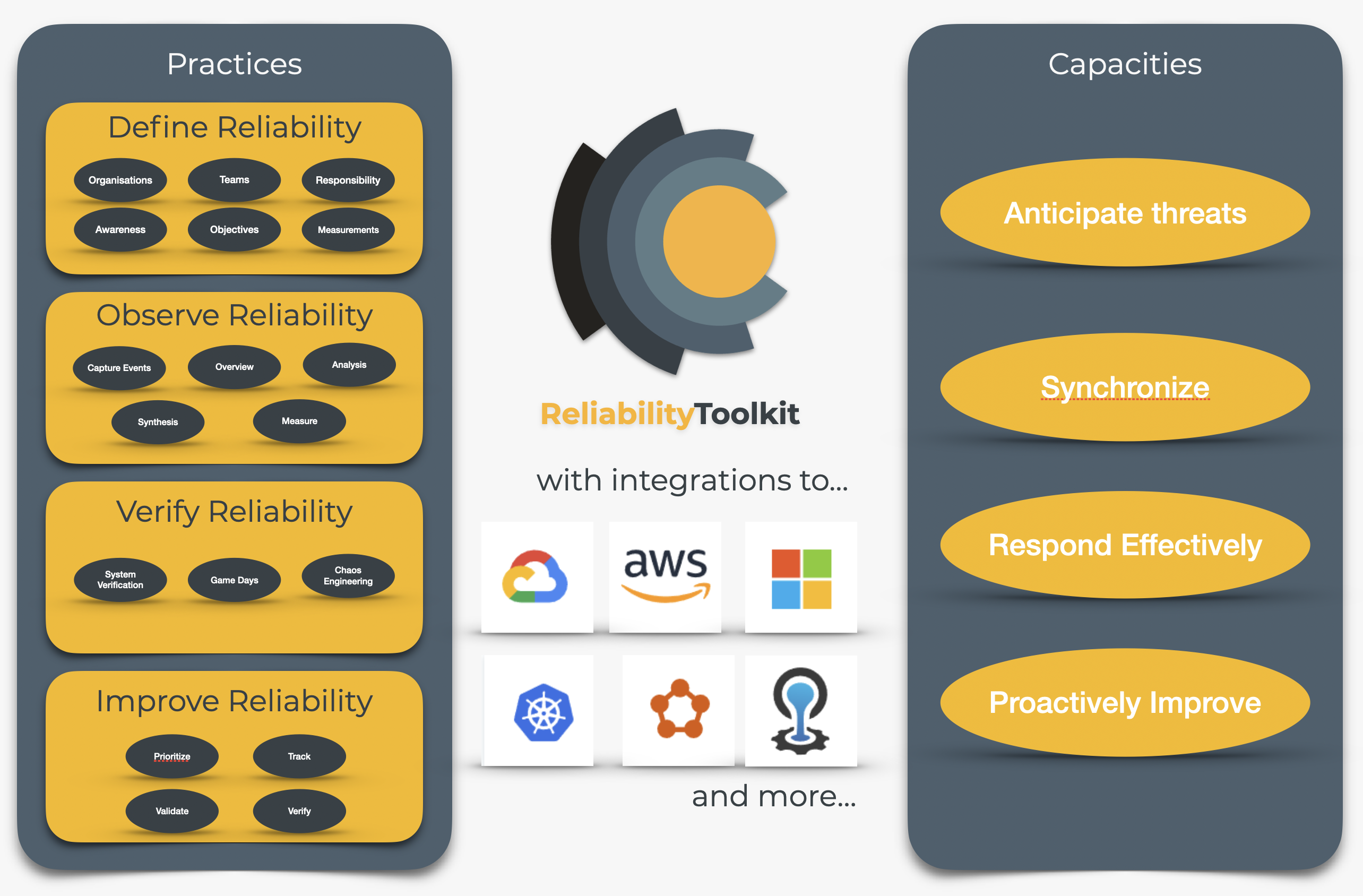

You and your team will invest in practices to develop capacities. To do this you will establish your own Reliability Toolbox and practices to help you explore and develop your system’s ability to anticipate, synchronize, respond and generally adapt to unexpected conditions.

Practicing reliability brings together principles, tools and techniques from multiple sources including resilience engineering, site reliability engineering, DevOps, DevSecOps, effective operations, incident response, and system observability. You don’t need to be an expert in any of these, but by beginning to practice reliability you will gradually adopt useful parts from each as you choose to invest the right amount of time and resources in developing your system’s resilience.